As published in the February 2019 issue of An Cosantóir

Report & Photos by Sgt Wayne Fitzgerald

Athy, Co Kildare, is a thriving market town located approximately 65km from the Red Cow/M50 junction and 22km from the Curragh Camp and is the place where the River Barrow and the Grand Canal meet. Athy became one the initial Anglo-Norman settlements after Richard de Clare (Strongbow) granted the area of Le Norrath to Robert FitzRichard in 1175, and other Anglo-Norman lords, including Robert St Michel, settled on the surrounding lands. At the beginning of the 13th century, the St Michel family built Woodstock Castle, and it was outside this castle that the first Anglo-Norman settlement developed. Subsequently burned and sacked a number of times, it is believed the town was walled as early as 1297; walls that were maintained until well into the 15th century.

One famous local resident was renowned Antarctic explorer Ernest Shackleton, who was born in nearby Kilkea. The intrepid explorer is honoured and remembered with a whole floor dedicated to him in Athy’s Heritage Centre, which is based in the old Town Hall on Emily Square. (Visit www.shackletonmuseum.com)

When I visited the Heritage Centre I met with local historian Clem Roche, who took me through the town’s military history, which predates the establishment of the Curragh. Clem has researched the exploits of Athy men through many wars and told me that they have been serving in the military since the 1730s.

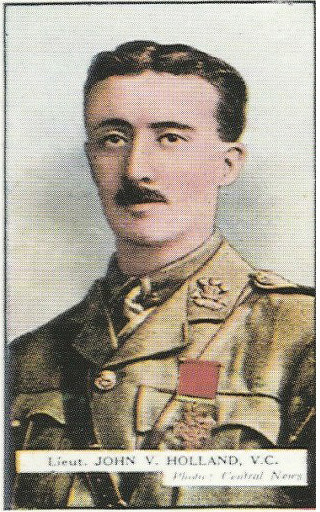

The story that caught my attention was that of John Vincent Holland, born in Athy in 1889, who won a Victoria Cross (VC) in World War I. Holland attended Clongowes Wood College near Clane, Co Kildare, studying veterinary medicine for three years before leaving in 1909 for a more adventurous life in South America, where he tried his hand at ranching, railway engineering and hunting. On the outbreak of the Great War, he returned to Ireland and was commissioned as a lieutenant into the Leinster Regiment. He was wounded at the second battle of Ypres in 1915 but recovered to take part in the Somme campaign of 1916, serving as a bombing officer with the 7th Battalion of the

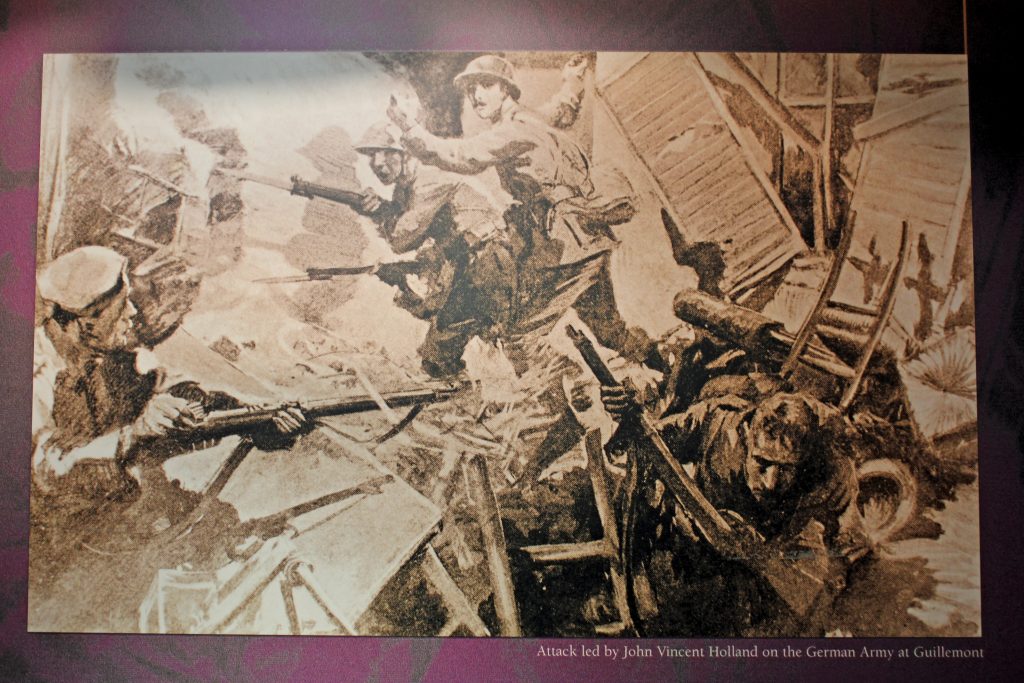

On 3rd September 1916 he played a crucial role in the capture of Guillemont, which was rated as one of the great achievements of the 16th (Irish) Division, and was subsequently awarded a VC for:

“most conspicuous bravery during a heavy engagement, when, not content with bombing hostile dug-outs within the objective, he fearlessly led his bombers through our own artillery barrage and cleared a great part of the village in front. He started out with twenty-six bombers and finished up with only five, after capturing some fifty prisoners. By this very gallant action he undoubtedly broke the spirit of the enemy, and thus saved us many casualties when the battalion made a further advance. He was far from well at the time, and later had to go to hospital”.

Holland, clearly a modest man, attributed his award to “the fidelity and extraordinary gallantry” of the men he commanded. On his return home, he received a civic reception but did not remain in Ireland. He served for a time in the Indian Army, returning as a major during World War II. He finally settled in Australia, where he received a state funeral after he died in Hobart, Tasmania, on 27th February 1975.

It was my interest in this VC winner that initially brought me to Athy to find out more about its military past. This led to my meeting with some of the veterans who had started St Michael’s ONE branch in the town, one of the newest branches in the veterans’ organisation. The branch, which was established nearly five years ago and has 12 full-time members and seven associates, takes its name from the parish of St Michael’s, which in turn takes its name from the St Michel family mentioned earlier.

For the first four years, St Michael’s Branch held their monthly meetings in Dominican Hall and Methodist Hall on the Carlow Road before moving to Athy Community College (with many thanks to Principle Richard Daly) for the last year.

I met with several members of the branch to get some background. Branch Chairman Kevin Carton, originally from Wicklow, spent his career with the Transport Corps in the Curragh. Branch Secretary John Roche, an Athy native who comes from a large military family, served with the Ordnance Corps, also in the Curragh. Other branch members at the meeting were Anthony Davis, formerly Medical Corps; Pat Roche (John’s brother and the father of Clem, the local historian who had been my guide in Heritage Centre) formerly Artillery Corps; John Lawlor, from Athy, formerly of the Engineer Corps; William Lawlor, who served in the Curragh and Dublin; Liam Foley, from Athy, who served in the Military College; and John Roche’s wife Kathleen and his other brother, Michael, who are associate members.

At the start of our meeting, the branch members paid tribute to Raymond Clarke, one of their founding members, who sadly passed away three years ago. Raymond had served with An Slua Muir and

John recalls the meeting held in 2013 in Fingleton Auctioneers in the town to see if there was sufficient interest and ONE CEO Ollie O’Connor came along and spoke to those present. There was great interest and Kevin says: “Starting off it looked good with numbers.” Of course, though, starting off any venture like this provides many challenges and obstacles to overcome so it was by no means easy but all agree it was worth the effort.

The branch has an excellent Facebook page that lets people know what they are about and to share photos of events/projects they are involved in. One of those projects, cleaning and renovating the grotto on the Monasterevin Road, has earned great acknowledgement for the branch. Due to the branch’s efforts the grotto, originally built in 1954 by the Lower St Joseph’s Residents’ Association, now includes a roll of honour for the 87 members of the Defence Forces who died on overseas service, and has won numerous awards, including the Athy Tidy Towns Award in 2016 and again in 2018, jointly with another location.

Among the branch’s many activities last year, they took part in the town’s St Patrick’s Day parade and provided a guard of honour for the visit of the Rose of Tralee. The branch does a fair amount of annual fundraising, including holding a number of raffles, collecting for ONE’s Fuchsia Appeal and lotto draw. Their local charitable work includes donating large, framed pictures to St Michael’s Parish Church, and plaques in the old and new graveyards.

Branch, ONE

As a result of all of the above, this young branch has already made an impact locally. John said the branch receives very positive feedback in the town for their charitable work. In recognition of its community spirit, St Michael’s Branch became the first ONE branch to get a civic reception when they were given one by Kildare County Council in March 2018, at which the branch gave a presentation on the Fuchsia Appeal to the councillors to make them aware of the plight of veterans.

Looking to the future they would like to increase their membership numbers over the coming year and have been in discussions with their local councillors for assistance for a suitable building they could turn into a Veterans Support Centre (VSC),

I was very impressed with the comradery within the branch and by the respect in which they are held locally. It was also good to meet the members in person after having come across them at many veterans’ events over the years.

Read these stories and more in An Cosantóir (The Defender) The official magazine of the Irish Defence Forces – www.dfmagazine.ie.

The gardens, which are located on the southern banks of the Liffey about three kilometres from the centre of the city and occupy an area of about three hectares, were designed by Sir Edward Lutyens.

The gardens, which are located on the southern banks of the Liffey about three kilometres from the centre of the city and occupy an area of about three hectares, were designed by Sir Edward Lutyens. Enclosed within a high limestone wall with granite piers is the central lawn, the centre of which is a Stone of Remembrance made from Irish granite. (Lutyens designed the Stone of Remembrance for the Imperial War Graves Commission. It was designed to be used in IWGC war cemeteries containing 1,000 or more graves, or at memorial sites commemorating more than 1,000 war dead. Hundreds were erected following World War I.) The Stone of Remembrance symbolises an altar and is flanked on either side by fountain basins with central obelisks symbolising candles. The combined symbolism of the altar, candles and cross is representative of death and resurrection.

Enclosed within a high limestone wall with granite piers is the central lawn, the centre of which is a Stone of Remembrance made from Irish granite. (Lutyens designed the Stone of Remembrance for the Imperial War Graves Commission. It was designed to be used in IWGC war cemeteries containing 1,000 or more graves, or at memorial sites commemorating more than 1,000 war dead. Hundreds were erected following World War I.) The Stone of Remembrance symbolises an altar and is flanked on either side by fountain basins with central obelisks symbolising candles. The combined symbolism of the altar, candles and cross is representative of death and resurrection.

The Ginchy Cross is also housed in one of the book rooms. This wooden cross was erected in 1917 as a memorial to almost 5,000 Irish soldiers of the 16th Irish Division who were killed in action at Guillemont and Ginchy during the battle of the Somme. The cross was later replaced by a stone one and the original was returned to Ireland in 1926.

The Ginchy Cross is also housed in one of the book rooms. This wooden cross was erected in 1917 as a memorial to almost 5,000 Irish soldiers of the 16th Irish Division who were killed in action at Guillemont and Ginchy during the battle of the Somme. The cross was later replaced by a stone one and the original was returned to Ireland in 1926. In 1988, after a period of extensive restoration the gardens were rededicated to the many servicemen that lost their lives in both world wars. The Office of Public Works (OPW) now manages the Irish National War Memorial Gardens in conjunction with the National War Memorial Committee.

In 1988, after a period of extensive restoration the gardens were rededicated to the many servicemen that lost their lives in both world wars. The Office of Public Works (OPW) now manages the Irish National War Memorial Gardens in conjunction with the National War Memorial Committee.